They Need, Like, Us

In some ways, I feel like I've gotten my attention back. A few months ago, after researching and writing some pieces about Meta, I decided to come off of my Facebook and Instagram accounts permanently. Combined with my abstinence from TikTok, my use of social media has become less "social" and more "media" as I have replaced these platforms with Bluesky, Reddit, and increased YouTube usage. I primarily engage with my friends over texts and video calls; I primarily engage with world news and culture via these apps.

But as I have shifted my attention, I have arrived at some observations about the very concept of attention that feel relevant to the kinds of things you guys tell me you like reading about.

Attention is the final frontier of resources to mine. In a world of (relative) abundance, there are always only 24 hours in a day, around a third of which people spend sleeping. As more and more screens enter our lives, more and more avenues for revenue get piped right at us. In 2017, Reed Hastings, the then CEO of Netflix, implied that one of the streaming giant's competitors is not other streaming platforms but sleep itself, saying "We are really competing with sleep on the margin."

The race to strip mine human attention has yielded all types of bizarre creations, like backseat taxi ads, or short form algorithmically recommended video, or premium tiers not to see no ads but to see fewer ads.

Today, I want to make an argument, perhaps even just to myself, that our attention is often not worth these exchanges. Human intellect and awareness provide us with so many meaningful experiences, like going down a Wikipedia rabbit hole or simply laughing with a loved one while watching TV. But the benefit of giving up our time to that which enriches us is being exploited by anyone and everyone, and it might be costing us democracy.

King Kendrick

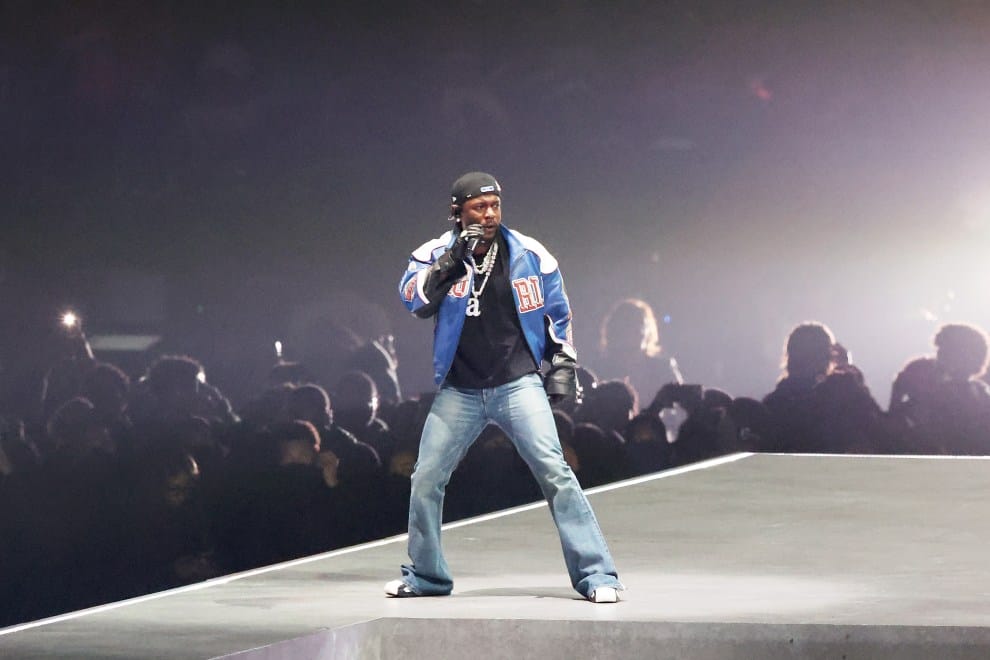

This is an excellent behind the scenes look of the development and logistics that went into producing Kendrick Lamar's halftime show back in February. In thirty minutes, we track from the selection of Kendrick as the performer all the way through to striking the set after the performance.

One thing that struck me while watching this was just how many people there are who made it happen. Here are some of the numbers from this video:

250 fabricators: In just one of the shops that constructed the video game controller inspired sets, one person mentions that 250 people aided in the fabrication.

500 movers: When the coordinator of the in-game setup and strike talks about the effort to hustle the entire set in in just a few minutes he says that the caravan stretches a quarter mile. You can watch, in this video, some of the people who marched Kendrick's set onto the field.

400 dancers: According to one of the creative directors, there are around 400 dancers used in this performance.

In just these facets of the process, that is over 1,000 people. This isn't even including the camera operators, the production team, wardrobe, or MUSTAAAAAAAAAAAARD.

One production company, All Access based in Los Angeles, worked through devastating wildfires to construct the set, putting in over 15,000 working hours. A few enormous trucks had to drive the set for over 24 hours for hundreds of miles on Interstate 10 from LA to NOLA. (Small, qualified shoutout to Dwight Eisenhower!)

It could be said of every recent Super Bowl halftime show, but this effort is mythic. It calls to mind the caravans of ancient Pharoahs, the trudging marchers carrying the royal palanquins of Dynastic China. A nigh-religious, world bending effort for...13 minutes of performance...between two halves of a football game.

Why? What could possibly justify the dizzying numbers, the flurrying hands, the human ingenuity? How could 13 minutes on a Sunday evening matter this much?

It is for the same reason that 30 seconds of advertising time can cost millions: the Super Bowl draws a lot of attention. With over 85,000 people in the stands, including some of the world's wealthiest, over 130 million watching from home, and (as of publishing) over 117 million YouTube views on the halftime show, the Super Bowl is one of only a few instances in which advertisers and broadcasters can trust that they have people's attention. Apple knows that there is no more premium 13 minutes in a year to have their name associated with one of the world's biggest musical acts, which is why they are spending somewhere in the neighborhood of $50 million a year to sponsor the halftime show. That's around $3.85 million per minute of the broadcast.

Consider the profundity of this, though. No one is being forcibly compelled to give their attention to the Super Bowl. This exchange is unlike most other economic bargains for resources or labor. They give us something to pay attention to, and we pay attention. That's it.

But what if we just stopped? What if some cultural shift draws attention away? Does anyone still pay $50 million to slap their name on it? Are 250 union fabricators still employed in Southern California?

Looking away

Google, Meta, TikTok; these are advertising companies. Sure, they make all sorts of things, but the vast majority of their revenue comes their advertising platforms. Every minute they are trying to guess what your Super Bowl Halftime Show of the day is going to be. From moment to moment, by tracking your digital footprints, they win when your screen shows their logos, their ads. Your phone can tell you how much of your attention you are freely giving these companies down to the minute.

I think I am risking getting a little too preachy. I want to make clear that I am not saying that freely giving up your attention is inherently a bad thing. In fact, interacting with friends, enriching your day with something you love watching or playing, and learning about current events are all pretty great ways to deploy what little attention we have. But what I recognized after deleting these apps and having to find new places to put my attention is that the trade off - what I get from them and what they get from me - is not balanced.

Recently, family members of mine attended a timeshare presentation being done at a hotel. For an entire hour of their blessed lives, they had to sit through a sales lecture for something they had no intent on investing in. But after it, they got a voucher equal to $1000 off their hotel stay. In this situation, the trade off made sense.

Online, though, they are extracting my location data, and my search history, and my political preferences, and my favorite sports teams, and my familial relationships, and my spending power, and my fandoms, my rage and my hope. And what do I get back? A funny meme here, a compelling observation there. A comment here, and heart react there.

Since I've been away from the apps, I've learned that my attention is far more valuable than I gave it credit for. I've begun to see how online gambling companies and political figures alike are attempting to seize on these imbalances to nudge me in one direction or the other. I've observed how easy it is to exploit attention, and how hard it is to catch it happening to yourself.

There is a bleakness to these conclusions, one that greys the outlook for the future. As more and more people are introduced early to these attention mining systems, we risk wide scale deficits in our collective focus on issues that genuinely and actually matter. I worry about what this could mean, and what a world in which The Attention President continues to act on his whims will look like in two, four, ten years.

For now, even if it's just in our little Arachne corner of the universe, I will continue to honor the attention you spare to read these pieces. I am so grateful that you do.

The journalist Chris Hayes has a book out called The Sirens' Call: How Attention Became the World's Most Endangered Resource. I know that there is a lot of overlap between the ideas I am meditating on here and the ideas in this book, and I was wondering if anyone would want to do a little book club for it. You can let me know if you are interested however you want.