How could it take so long?

Following the surprise shooting of a healthcare CEO in Manhattan last week, one of the questions I kept asking myself revolved around technology.

How could a person shoot someone in midtown Manhattan and evade both identification and apprehension?

For days, a few details were reported that only further made this question more intriguing.

They knew he took a bus into and out of the city, but they don't know where he is. He rode an electric Citi Bike into Central Park, but they don't have a name. They knew he was seen on video holding a cellphone to his ear minutes before the shooting, but they don't have a potential accomplice.

These are all details that could only be obtained thanks to an intrusive, elaborate web of technology that covers, like, every inch of the island of Manhattan.

It may be accepted as axiomatic that no one is really anonymous anymore, that nothing ever truly gets deleted off the internet, and that everything you do is being tracked. But if a person can shoot someone in Midtown and get out of the city before anyone even has a name, there are, evidently, limitations to the kind of surveillance Americans have come to accept. So, with all that in mind, lets chat about why it took almost a week to find the guy.

Not to brag(!), but I had a hunch early on that the shooter would be someone with technological understanding beyond the average citizen. There were a few things that tipped me off:

- The backpack. The makers of the bag, Peakdesign, are favorites among tech and tech adjacent folks. You tend to see it in "daily carry" videos from YouTube creators.

- The anonymity. For someone to obfuscate their identity while doing things like riding Citi Bikes and (allegedly) chatting on the phone minutes before the shooting, they would have to be aware of the manifold ways in which these activities could be tracked. Credit card information - not the kind that could be used to purchase things, but the kind that could be used to identify someone - is not that hard to come by. Same with phone logs. This individual would have to be someone who knew how to cover their tracks.

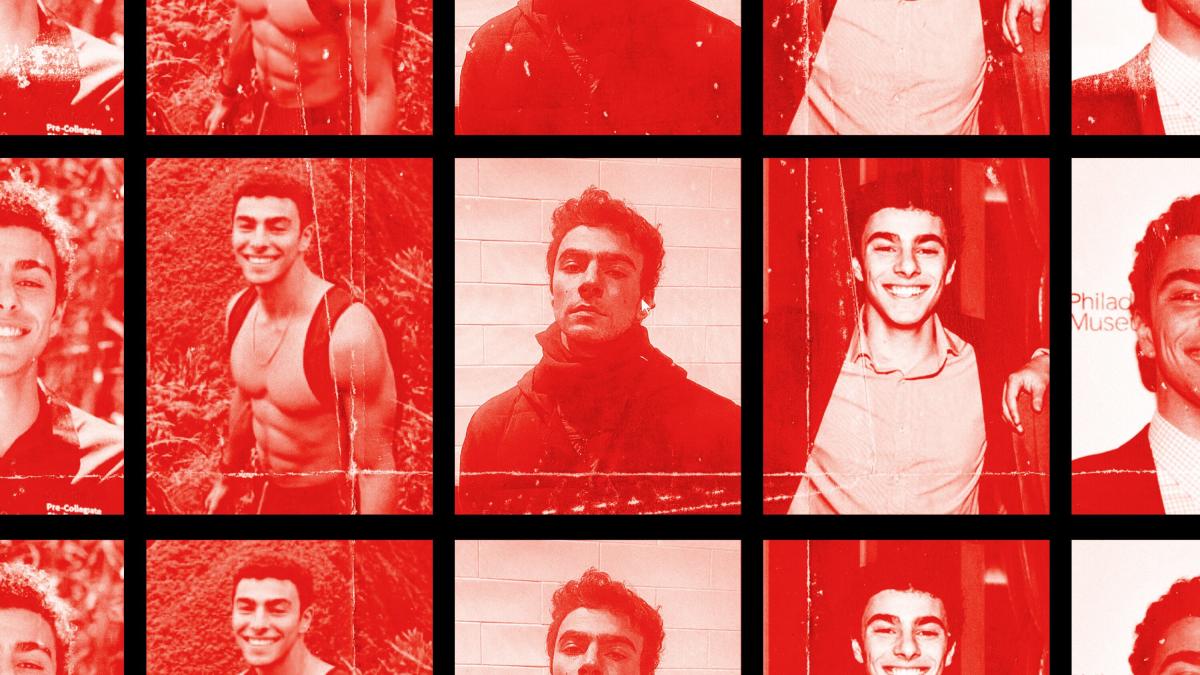

After more details emerged on Monday, my hunch was proven correct. The guy is a technology professional, having worked multiple tech and software engineering jobs.

Now, if you're into the kind of armchair analysis that I am, you may have found yourself wondering over the last few days whether the guy did or did not want to be caught. Some may argue that the public nature of the crime, the symbolic attention given to the words on the bullet casings, and the new detail about a so-called "manifesto" demonstrate a desire for notoriety and acknowledgment. But there are several other details that tell me this guy did not want to be caught and identified, at least not immediately, and they all involve an understanding of tech in some way.

First, there's the weapon. Not to alarm you, but it is remarkably easy to build your own firearm in this country. These sort of weapons are referred to as "ghost guns." By obtaining miscellaneous parts, manufactured and 3D printed, it appears this guy made his own pistol with a silencer. With a ghost gun, you don't need to scratch off the serial number. There is no serial number. If you want to be caught, you don't DIY your own gun.

Then there's the escape. Let alone that there even was an escape, the methods he used demonstrate an understanding of surveillance technology and a desire to disappear. Surveillance these days is more than simple CCTV cameras, and it is evident that this individual knew this. From the hostel, to the bike, to the beeline for Central Park (no, the pigeons are not camera equipped), to the uptown bus terminal, multiple decisions were made to evade observation and tracking. These are methods of travel that can be achieved nimbly, with cash in some cases, and without much digital footprint. Especially, as I argue, if one already knows where to smudge the tracks.

Next, there's the social media details that have since emerged. On Monday, the shooter's (public!) Instagram profile, Linktree page, and Goodreads account all went viral and my screenshot fingers went crazy.

Now Alex, you may ask, and I thank you for asking, if this guy wanted to disappear, why would he have a public Instagram with pictures of him with his frat brothers and a Goodreads account with multiple lengthy book reviews on it? All attributed to his name?

It's a good point, but I think it's possible that months and years of digital footprint were scrubbed in the lead up to the shooting. And there is further evidence of this:

As the article above puts it, the shooter had gone “radio silent” over the summer. Of all of these accounts, the most recently updated one is Goodreads: May 2024.

Ultimately, though, I think that the incredulity at how long it took to apprehend the guy, both mine and the public's, is informed by a broad misconception about the nature of surveillance. Yes, there is a wide reaching and invasive surveillance apparatus in place in this country, but media, copaganda, and our own cognitive biases have given us the impression that it simply "works." Some incorrect assumptions we have include that our phones are always listening to us or that there is a facial recognition database that can just figure out who someone is.

It is foolhardy to give the government too much credit. While the ocean of data is clear to see, it's difficult to pull out the one right drop. While surveillance presses onward - we are unique in our country's lack of a federal data privacy law - it will continue to battle the everyday entropy of street level life.

As details emerged about the shooter on Monday, I was struck by the number of Regular-Ass Dude stuff that existed about him. Yes, there were the insanely weird takes on Japanese culture, which I won't link here, but what digital footprints exist point toward a pretty typical mid-twenties white guy in tech. He's read a number of the pop-psych books that allow narrow and inexperienced minds to claim a sort of intellectual seriousness that neither the authors nor the readers have really earned. Diet and exercise guides, Outliers by Malcolm Gladwell. Okay, yeah, and the Unabomber book.

This is somebody who thinks of himself as smart, whose prefrontal cortex kitchen timer was about to ding, who formed a worldview while the pandemic isolated and emotionally stifled everyone and drove life onto the screens. Like anyone, this person was probably insecure about his body, his mind, but ensnared too deep in questions of modern masculinity and digital society to realize it.

As the days passed and we still didn't have a name, I was increasingly certain they wouldn't find the guy. My main question, the one that tipped off this post, revolved around how it was possible they couldn't identify him and find him in today's technological landscape. But then they found him, and my questions changed. Now I am curious how to identify and find myself in today's technological landscape. In a sense, that's a goal of this newsletter project, to find the pro-social crannies and the connective tissue of our shared digital experience. In remaining skeptical and optimistic, we can promote the many ways that technology brings us together without government or corporate intervention.

There are a number of reasons why someone would not want to be tracked and surveilled, many of which have absolutely nothing to do with violence or criminality. For this reason, there are many resources online for people that want to limit the corporate and government overreach we are faced with every day. But whether or not we want to be caught, the motivations that bring us to our most deeply held beliefs; these are not technology problems, these are human problems that technology often gives us shortcut answers to.

This post has no grand unifying theory, no oracular verdict on What It All Means. It's just a reminder to myself that our tech ecosystem of government and corporate interests does not always have human interests at heart. And when confronted with unpredictable and challenging human life, technology's easy answers are not always the right answers.

One last thing: