A Lot of Stuff Looks Like Journalism

But is not journalism.

It may or may not be obvious, but we have a serious information problem. Education in media literacy has not matched the pace of media proliferation, resulting in problems ranging from the trivial to the democracy undermining. We do not have a really functional information economy. Not because the work of skilled, well-resourced journalists and researchers has gotten worse, but because the work of unskilled and alternatively motivated contributors has gotten better.

What do I mean by this? If we go back a couple decades, even just to the late 90s and 2000s, there was a clear delineation between Real And Serious Journalism and Everything Else. It was most evident in the medium by which people received their news. If it was on TV on the nightly news or in the newspaper the next morning, audiences could trust that what they were being told had a supporting structure of credibility. While there are certainly reasons this was not entirely true, radio, television, and newspaper syndicates spent decades earning the trust of audiences through rigorous, professionalized work. Since the halls of media power are as self-congratulatory as they are self-important, we've even gotten multiple Oscar winning movies about the thankless work of professionals who exposed the cover-up of decades of child abuse in Boston (Spotlight) or got to the bottom of the Watergate scandal (All The President's Men).

When these main avenues for information were dominant - radio, television, newspaper/magazine - it was easier to differentiate legitimate from illegitimate information. If you came across a flyer that told you lizard people had infiltrated the federal government, if you saw a tabloid magazine cover that told you the Yankees won their exhibition game against the Martians, if you clicked through a shoddy homemade HTML site that told you the fluoride in your water was chemically castrating you, the mere fact that it wasn't in the more trusted venues for information may make you an inch more skeptical of what you were reading.

But, obviously, the internet has completely overturned this hierarchy. I want to clarify upfront that I say this not as a judgement or as a statement in support that one system of spreading information is better or worse than the other, merely to point out this fact. Everything is online now. On TikTok, for example, you may view one video from the well-resourced and salaried workers at The Washington Post explaining a current event and the very next video could be a person you've never seen before explaining the same current event. There is no differentiation, and the human brain is not constructing a serious line between the first video and the second video.

It's extremely important for me to point out that I am not necessarily saying that the work of legacy media companies is inherently better than the work of your favorite independent internet personality. It is abundantly clear, and certainly has been in the last year and change, that the legacy media institutions will often prioritize the perspectives of those in power over the marginalized and oppressed.

I say all of this to elucidate what I think is a largely ignored facet of our chaotic media ecosystem. To me, it is not particularly important whether or not there is more or less ridiculous bullshit finding its way through the manifold channels of the internet to peoples' eyeballs and ears. It is more important that the incentive structure of the media industries is completely, utterly, entirely fucked.

Influencers are not journalists

Bad faith contributors to the information economy have gotten much better. Their websites look just like the websites of more legitimate outlets, their podcast setups look just like Larry King, their digital assets, their video editing, their relationship with powerful people...

It is all a construction to give the message a sense of legitimacy, rigor, and independence that signals to audiences "You can trust this." Consider Alex Jones and InfoWars. If a red and veiny man was screaming at you from his basement on a 480p resolution stream, you might question that guy's motivations, you might make assumptions about what his life is like beyond the spittle and roid rage. But put that guy in a shiny studio that looks like CNN, give him a blazer, get someone to touch up his makeup between takes, and suddenly you have all of the airs of credibility. Suddenly, claiming that the children killed at Sandy Hook were actors has the same polish as Anderson Cooper.

Suddenly, advertisers of snake oil supplements and tummy trainers look upon that stream as a viable place to capture customers. Suddenly that money is funding a growing alt-right media empire. And the snowball picks up dollars and audience and rolls and rolls down the hill.

But Alex Jones is not a journalist. He is not even a truth seeker. Alex Jones is an opportunistic loud mouth that used his skills, a broken incentive structure that privileges views and engagement, and the internet to become influential.

Jones is obviously an extreme example, but there are countless individuals online across all verticals - tech, product reviews, sports, etc. - that use basically the same playbook in order to win audience attention, convert that into advertiser dollars, and become prioritized sources of information for the population.

The influencer economy privileges influence, not integrity. You win influence by winning engagement. You win engagement by saying outlandish things, doing ridiculous stunts, and cozying up to whoever you can put in your thumbnail to get people to click.

Pundits are not journalists

I stopped watching cable TV news a long time ago. I cringe and recoil at the vision of four heads in rectangles, a chyron that reads "MAYBE BIRTHERISM MADE A FEW GOOD POINTS," and any program called like "Hardhitters," "Do Not Pass Joe," or "Friendly Fire." The thing I find most intolerable, though, is the utilization of so-called "experts" to "debate" whatever the topic of that three and a half minutes is before the pharmaceutical commercials play.

We call these people pundits. They are brought on television as authoritative voices on some kind of issue, allowed to say the dumbest shit possible, and run it all back the next day when some other non-controversy makes its way to the producer's desk.

Often, though, this authority is not earned. It is simply awarded to whatever guileless stooge is most willing to inherit the talking points of whatever sports team or political party they are there to stump for. Under the lights, in the suits, these people are allowed a credibility that ought to be questioned.

Take, for example, the recent fracas caused by loser Ryan Girdusky, who made the incredibly racist "beeper" comment to Mehdi Hasan in a CNN roundtable just before the election. Every possible piece of evidence a booker on a television news program would need to know that Gidursky is a hack, is not interested in good faith discourse, and was only showing his face to garner favor with the Republican elites was easily findable. You can go to his own website to see the multiple television appearances he's made in which he just opens the spigot on the kind of nonsense that engages viewers that agree with him and enrages viewers that don't.

It's not just on television though. On the major social media platforms people assert their expertise in countless unchecked ways. It happens when the person speaking says something like "Do you have neck pain? Hi, I'm a doctor that specializes in spinal injuries" without disclosing to you that they are actually a chiropractor, not an MD. It happens when Joe Rogan invites some self assured dickhead on his podcast to talk about how your wireless Xbox controller is giving you ball cancer.

At the end of the day, pundits are not legitimate contributors to public discourse. Their influence and authority is granted not by the credibility of their work, but by the stakeholders that are made more powerful and companies made more rich.

I am not a journalist

Despite my best efforts to write quality newsletters that are well researched, I am not a journalist. I do not have an educational background in journalism. I do not have a formalized code of ethics that I follow or an institutional style guide. Considering I don't currently have a job I imagine I would be pretty easy to buy if some advertiser came my way. But there are other ways I hope to engender your trust. For most of you that trust comes from the fact that you literally know me lol and knew me before I ever started writing Arachne.

But this offers me a great moment to stop and offer you some media literacy tips. Here are some questions I hope you will think about when engaging with information online:

- Who wrote this?

- How is this funded? Ads? Subscriptions? Non-profit? Corporate sponsorship?

- Who benefits if what I see here is true?

- Who benefits if what I see here is half-true?

- Who benefits if what I see here is false?

- Have I heard of this writer/creator/influencer or outlet before?

- Does this information have a source?

- How does this information fit into my understanding of how the world works?

- Do I have a model for understanding how the world works?

- Is the information affirmed by common assumptions?

You can deploy questions like this for so much that you see. You can do it for Arachne. You can do it for Pop Base tweets, you can do it for sports, for politics, for anything you see. It is important as a practice to constantly be thinking about yourself as someone who can be influenced. Once you consider that you can be influenced, it is important then to unravel the countless ways different stakeholders are vying for your attention. I promise you they are thinking more about how to get you than you are thinking about how not to get got.

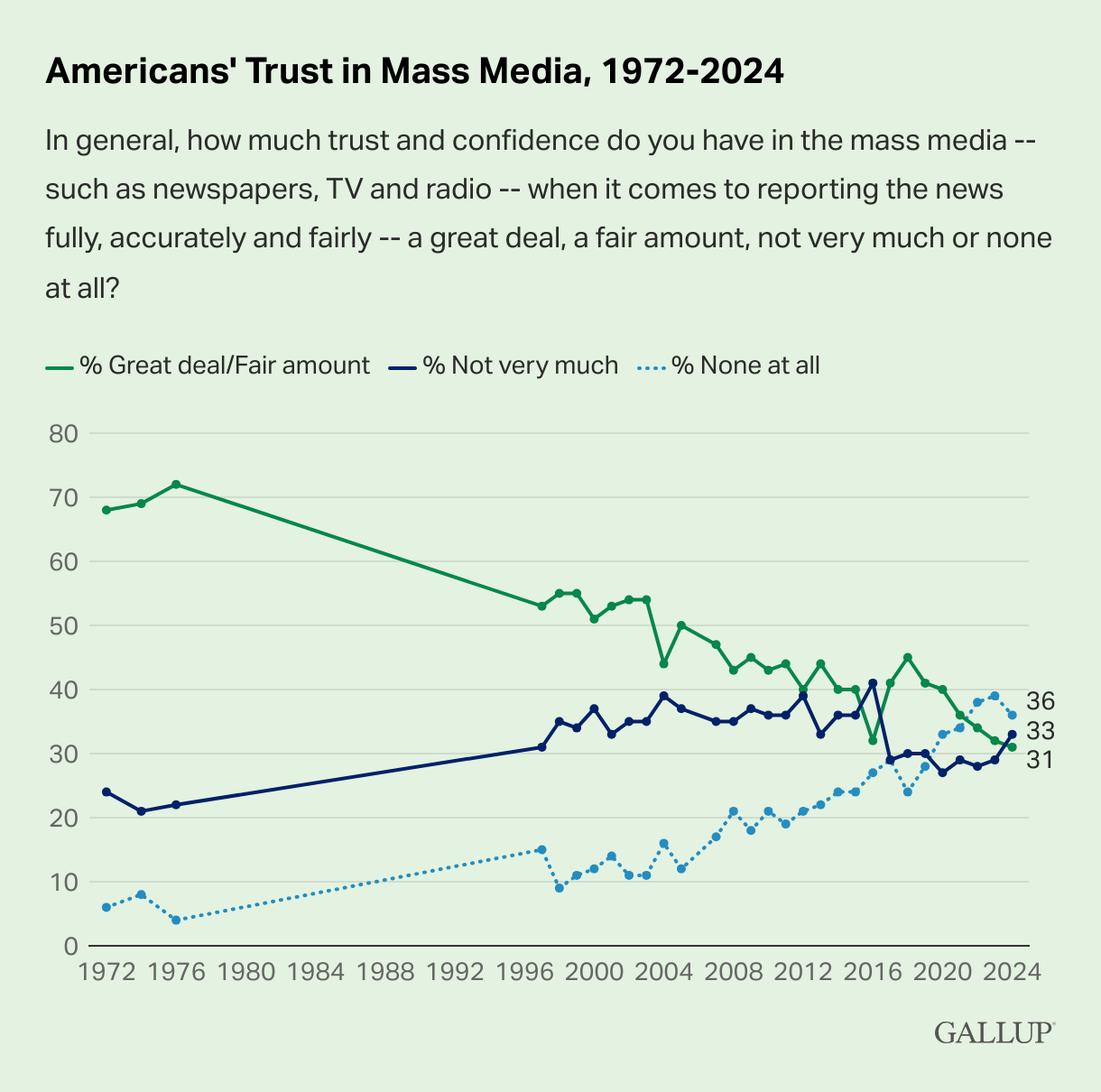

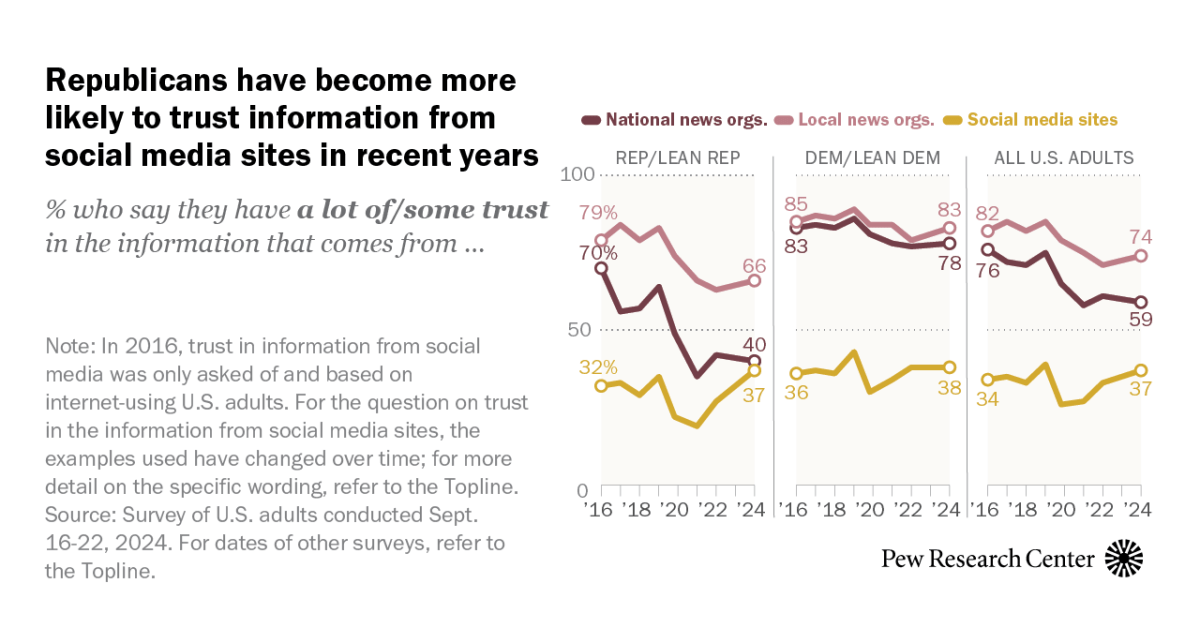

A much proliferated doomer topic of the media elite is this idea that trust in legacy American media is at an all time low. This is true!

But I want to point out something that never seems to garner as much panic and self-flagellation as the above problem does. Yes, American trust in mass media waning, but American trust in alternative media is growing.

Much has been written and eulogized about the fading influence of legacy media outlets, but not enough has been amplified about the ways that alternative methods of obtaining information - social media, meme pages, random newsletters your friends write - have grown. On these outlets, there is a much stronger incentive toward sensationalism, stunts, clickbait, velocity, and quantity. The very business model reinforces this. I think in order to correct for this swing, there are a few things individual consumers can do, individual producers can do, and large regulatory bodies can do.

What can you do?

For one, you can simply divest your attention from bad faith actors. On top of this, consider the questions I've asked above. You will begin to develop a standard for what you will engage with on the internet. Do not hold your favorite voices on the internet above your own developing standards for what you will accept. Approach your consumption of information with the same rigor you expect of the people producing it for you.

Build a practice of analysis that is grounded and substantiated by material reality. Do not construct your world view out of hypotheticals. Here are some places and people I engage with on the internet who not only demonstrate rigor, but also model ways in which we can engage with the world.

- New York Times Opinion writer Jamelle Bouie, who can be found on Bluesky, TikTok, and of course the New York Times.

- If Books Could Kill Podcast, hosted by Peter Shamshiri and Michael Hobbes. Found anywhere you get podcasts.

- Maintenance Phase Podcast, hosted by Aubrey Gordon and Michael Hobbes.

What can producers of information do?

As a person that produces information and media for public consumption, what is my responsibility in this landscape? This may differ for others but first and foremost for me is understanding my motivation. If I am genuinely coming from a mission-driven place, if I am constantly returning to why I feel the need to say all of this, I feel that my sincerity comes across. I feel a genuine drive to empower people and offer imaginative alternatives to the way things are. As of right now, I don't make money doing this, but to me the money would only be validation and reinforcement of the mission, not a mechanism for power and influence.

Influencers, pundits, journalists, vloggers, whoever you might get your information from ought to "start with why" more than we do. Then, of course, there's the rigor and research. You'd think this would come as a given, but listen to If Books Could Kill and you'll find that many people have gotten very rich and influential while just kinda saying things.

What can the government and the industry do?

First, influencers and online personalities should be required to do the kind of disclosures that institutions constantly do to make consumers aware of potential conflicts of interest. Currently when influencers get paid to talk about a product or feature it in their work, they are supposed to disclose that that is an ad. But that is not the norm, and it is certainly not enforced. It should be illegal, for example, to hawk your testosterone supplements on your own alleged news program.

Second, we can guarantee basic necessities to all Americans. I'm talking healthcare, child and elder care, education, housing, and basic income. This might not strike you as a clear one-to-one correlation, but a reason why fundamental aspects of our lives can be so easily undermined by the targeted and motivated campaigns of opportunists is that fundamental aspects of our lives are not guaranteed. It is far easier for RFK Jr. to convince audiences that Doritos are poisoning them when their needs are not being met. And on the side of the influencers, perhaps we would find fewer people motivated to feed their families by parading the Rizzler around if the ability to feed their families were guaranteed.

Third, we should admit and make clear the biases of all outlets, mainstream and alternative, large and small. There does not exist a media outlet that is unbiased or balanced in any meaningful way. The sooner the large outlets understand that they are not objective observers, and the sooner the small outlets understand that they are not just "telling it how it is," the sooner we can all understand that there isn't some large scale effort to pull the wool over our eyes and make us all sheep. There is just a broken system of incentives, haughty self importance, and a chaotic flurry for attention. If individual people cannot be expected to completely rid themselves of bias, neither can companies.

This ended up being far longer than I was expecting, but I am glad to have gotten it all down. A lot of fingers get pointed in times like this, and I think it's really important to remember that the world, including the internet, is material and real. And things that are material and real can be changed. For too long we have culturally traded our trust in professional information retailers for any engaging enough person with a selfie camera. While there are plenty of people doing important, rigorous work independent of the legacy media institution, this very fact allows those that are not to gain influence. That we have a system by which anyone can garner influence and money for their hot takes lifts both the people with good intentions and bad. We must work as individuals and on the institutional level to disincentivize the people who prey on the instability and chaos of modern life to make money, get brand deals, or become President.